One thousand four hundred and seventy-six years after her patron saint helped found the city (give or take a few), she stepped her boot-clad feet onto cobblestoned Argyle Street. Eliza knew nothing of the saint, nor of God really, but she knew the intuitive pull of this place. It wasn’t her home, she knew that, but it was more significant to her than her hometown had ever been.

She exited the cab, shouldered her camera bag, and stepped onto the curb. Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum rose above her, its red sandstone aged with the soot of the city’s industrial past. Glasgow had been the shipbuilding capital of the Western world, and the grit and hardness of its past was still evident in the faces of its people. But Kelvingrove stood proud and elegant, its Victorian grandeur in stark juxtaposition to the plastic Tesco and the Indian takeout shop across the street. Still, that contrast of old and new, of stately and derelict was part of the appeal for her. The buildings of her hometown rarely predated the late 1800s.

She walked into the museum, her eyes adjusting to the absence of the summer sunlight, and walked to the reception desk. “Hello,” she greeted the gray-haired receptionist. Elaine, her name badge stated. “I’m Eliza Hamilton, and I’m a student at the Glasgow School of Art. I’d like to take a couple of photos of the Dali painting for one of my courses if that’s okay.” The woman smiled and Eliza recognized the slight smirk as an acknowledgement of her American accent. Not just American. Southern.

“Aye, just no tripods or flash photography. And mind you don’t block other visitors from viewing it. That’s our most popular exhibit, but it shouldn’t be too crowded since it’s a Tuesday morning.”

Eliza smiled and nodded her understanding. “Yes, ma’am. Thank you.” She turned to walk toward the main hall, but Elaine called after her.

“Beautiful accent you have, miss.” Eliza turned back and smiled.

“Thank you. I like yours, too.” She didn’t mean the statement to be sarcastic. The Glaswegian accent had taken her the better part of her first year of university to even begin to understand; its quick cadence and interspersed Gaelic words stopped her mind from completely absorbing the meaning of any spoken statements.

She paused at the posted museum map and found the exhibit: Dali’s Christ of Saint John of the Cross. Scanning the open hall, she found the staircase and began to climb to the first floor.

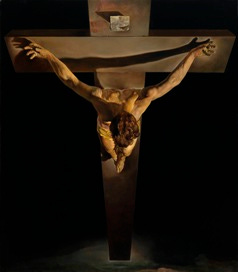

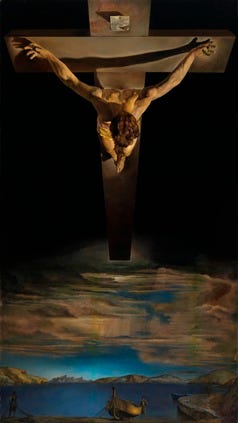

The assignment for her advanced photography course was to present a familiar scene from a new angle. She’d been utterly stuck on the assignment, completely uninspired, when her professor had suggested she visit the Dali painting. The painting depicted Christ’s crucifixion but, rather than viewing Christ from the front as most artists throughout Christian history had depicted the scene, this painting showed Christ suspended in darkness below the viewer. A simple boat was anchored at the shore of a calm lake below his feet. Literally, Dali had depicted a familiar scene from a different angle.

When she reached the top of the stairs, she walked through the exhibit doors and stopped. The painting hung directly in front of her in low light. Eliza let out a quick exhalation – her breath stuck as if she’d been punched in the gut. She sank down onto the bench in front of the painting and studied it. The muscles of his shoulders bunched and flexed unnaturally against the strain of his outstretched arms. His head hung, obscuring his face, and his fingers contorted and stiffened with the weight.

Completely unaware of the two other visitors, she studied the top of Christ’s head, his hair, and silent tears rolled down her cheeks. Rarely had art affected her to this degree, but her mind thought of nothing but the words, “It’s from his father’s point of view.”

Her Protestant upbringing had taught her all of the Bible stories, but she had left them in her childhood, understanding them only as creation myths and allegories. She hadn’t given them a second thought other than finding them useful to study the scenes of Renaissance paintings.

This painting, though, it was different. I am so undeserving, she thought as she looked at the straining muscles of his body.

She might’ve sat for hours, but a group of school-aged children filtered into the exhibit. Their prim school uniforms always surprised her; her school uniform had been jeans with muddy or ripped knees and hand-me-down t-shirts from her boy cousin. She glanced at the children and saw a look of concern pass a little boy’s face as he caught her eye and saw her tears. She quickly wiped them away, but he walked towards her. He sat down on the bench beside her and looked up, his smile revealing two missing front teeth.

“Ross! Back in line!” The boy’s eyes widened, and he jumped up and ran back to the line of school children.

Eliza waited until the children had milled out of the exhibit to take several photographs of the painting. She quickly placed her camera back into her backpack, turned her back on the painting, exited through the door and headed towards the stairs. She hesitated when she saw the group of children slowly descending the staircase, but she felt a deep need to be outside in the bright sun, to regain her footing, to know where she stood again. In Glasgow. In the West End. On a cobblestone street.

She recognized the boy, Ross, who had sat beside her, and as she reached his step, he reached his hand out to her. Without thinking, she grabbed the little hand and held it as they descended the stairs together. The kindness of his gesture was so simple and pure that she felt the tears well up in her eyes again. Haven’t cried in years and here I go again, she thought.

The group reached the bottom of the stairs, and she quickly squeezed his hand and released it.

“Goodbye!” the boy smiled and waved as she walked away. She returned his wave and sped up as she walked across the museum hall, opened the door, and quickly stepped into the bright summer sun.

I’m trying to write fiction again and, whewee, it’s been about as easy as getting back into shape. I have a story I want to write, but it’s not flowing. Practice makes perfect-ish, eh? Humor me, please. And honest critiques are always welcome. (For real.)

Here’s my comment: 😭 ❤️

Sorry, I’m a dull engineer.

It’s the best I could come up with.

Beautifully written.